Cocaine trafficking to Europe is rising sharply, with organised criminal groups increasingly exploiting commercial shipping and containerised cargo. Based on UN data and insights from Risk Intelligence, this article examines the latest smuggling trends and their implications for maritime operations and crew safety.

Written by

Diego Briceño

Analyst,Risk Intelligence

Published 08 January 2026

Gard recently provided an overview of cocaine trafficking as it effects commercial vessels, operations and crew. Based on the report from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, we noted the dramatic increase in the cocaine flows from Andean countries to Europe as compared with the traditionally largest market, North America.

The threat of drug smuggling has drawn the attention of international observers for many years. Concerns have steered towards the implications of drug seizures to commercial maritime operations as well as tailored-made recommendations on how to mitigate the consequences linked to drug seizures.

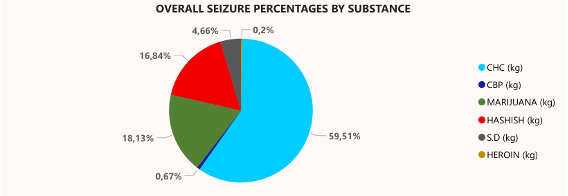

Cocaine trafficking in particular has developed into a significant global issue, which merits special attention. According to data from the International Centre for Research and Analysis Against Maritime Drug Trafficking (CNCOM), cocaine represents the highest proportion of drug seizures worldwide. Similarly, a joint report issued by the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA) and the World Customs Organisation (WCO) indicates that cocaine made up about 82% of the total amount of drugs intercepted at, or destined for, European ports between June 2019 and June 2024.

Overall seizure percentages by substance. Source: CNCOM 2024 Annual Report on Maritime Drug Trafficking

Geographical incidence of cocaine smuggling

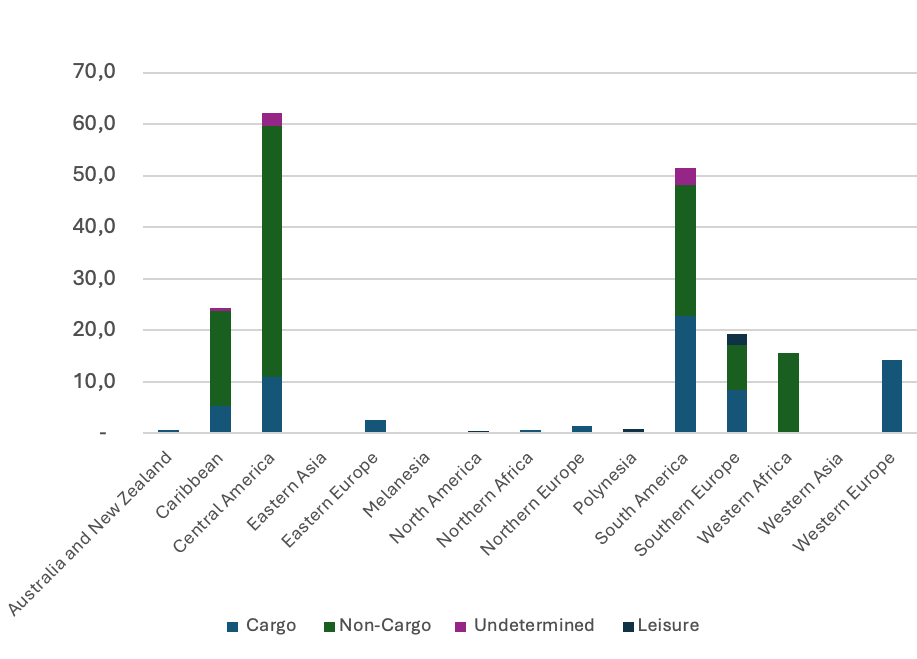

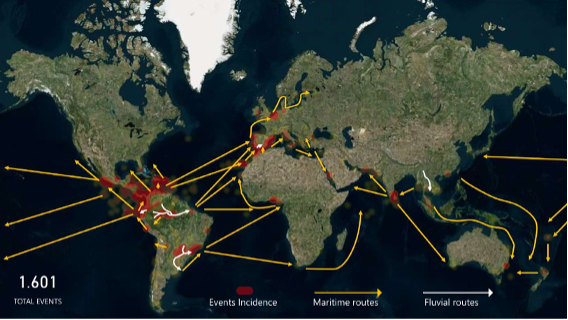

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) indicates in its 2025 World Drug Report that cocaine is mostly trafficked by sea, with nearly 80% of all seizures linked to maritime routes. Cocaine trafficking is mostly reported between South and Central American countries towards western European seaports, followed by maritime facilities in southern Europe. Central American countries also stand out as either departure points (e.g. Moin in Costa Rica) or transshipment hub such as Panama.

Tonnes of cocaine seized per region and vessel type in Q3 2025. Source: Risk Intelligence quarterly report on narcotics smuggling.

Although North America remains the largest cocaine market in the world, most shipments are smuggled via unregistered boats that cross the Pacific which explains the low amount of cocaine seizures. At the same time, it should be noted that seizures at distant locations have become larger and more frequent, with increased movement to areas where cocaine value surges.

Major ports such as Antwerp in Belgium, Rotterdam in the Netherlands and Algeciras in Spain serve as Europe's primary entry points for cocaine shipments originating from Latin America. These ports not only have reported unusually high individual seizures in recent years. They also account for most of the drugs seized in Europe. The primary reason is the size of these ports which allows them to serve as major entry points for goods headed to other European locations and as hubs with medium-sized ports throughout the continent.

Other European ports with significant cocaine seizures include Las Palmas, Gioia Tauro, Barcelona, Valencia, and Livorno. The ports in Amsterdam, Hamburg, Lisbon, and Vlissingen have experienced large variations over the years, possibly fuelled by increased drug seizures at Europe’s largest ports.

Source: CMCON, 2025. Annual Report on Maritime Drug Trafficking.

All statistics, however, suffer from a lack of reliable data. This is mainly due to reporting delays and limited access to public information. For instance, French officials confirmed the seizure of 47 tonnes of cocaine seized in the country through 2024, with 80% of the seizures reported at the port of Le Havre. Despite this information being public, there are inconsistencies with almost all available reports, including those issued by the EUDA or the WCO.

Gaps in seizure data largely result from public policy incentives. Latin American law enforcement agencies are prone to make drug seizures public as it allows them to demonstrate constant efforts in countering smuggling operations, hoping to retain or increase foreign aid. On the contrary, European counterparts have shown less interest in sharing information publicly as it would reveal awareness on current trends and counter-narcotics modus operandi.

South and Central American ports show high exposure to drug seizures. According to data collected by Risk Intelligence, about 65% of drug seizures larger than two metric tons were reported either at the points of departure (48%) – such as Ecuadorian or Colombian ports - or at transhipment points (17%), notably Panama which is located close to the main cocaine producing countries and plays a major role in global maritime trade.

Emerging smuggling trends

Overall, smuggling routes and methods have remained largely constant in recent years. However, criminal groups are constantly adapting to changing law enforcement patterns. Monitoring new methods and trends is therefore a key part of prevention efforts.

Containerised cargo continues to be the most relevant modality for commercial shipping, with most cocaine shipments departing from Colombia or Ecuador, followed by Brazil and Peru. Cargo contamination and the rip-on/rip-off techniques continue to be prevalent in South America, given the growing presence of organised crime groups around maritime facilities.

South and Central American authorities have purchased x-ray scanners to counter both threats. Although the adoption of this equipment has been crucial for larger drug seizures, smugglers are also known to have increased their awareness and adopted more flexible approaches.

For instance, Brazilian drug traffickers are increasingly using dry bulk cargoes to hide small cocaine shipments. This strategy not only reduces the risk of seizure as unpackaged cargoes are not scanned as shipping containers, but also allows criminals to profit from a series of successful shipments, even though some others are confiscated at port. Similarly, Colombian drug traffickers have also increased the use of legitimate cargo that is impregnated with cocaine diluted in organic solvents. These shipments are undetectable by x-ray scanners, which increases the reliance upon K-9 units.

Ecuadorian groups are often concealing cocaine within banana crates or frozen pulp fruit. While these cargoes are susceptible to being spotted by non-intrusive means, criminal groups are aware of the limited resources at port premises to review all scanned images. Furthermore, these groups have reportedly increased the level of infiltration within port workers either via bribes or death threats, triggering Guayaquil’s port authority to declare a state of emergency in August 2025.

Emerging concealment techniques are believed to explain the 2024 decline in cocaine seizures at key entry points such as in Rotterdam or Antwerp. However, there are also other trends that explain recent changes. The involvement of medium and high-ranking security officials within European smuggling rings was noticeable after the dismantlement of at least four of such organisations reported in the past months across Spain, signalling that smugglers are also prone to divert cocaine shipments to areas where law enforcement is less stringent, either because of low awareness or infiltration from organised crime.

Two additional trends are worth highlighting. The first one is the use of crew members to hoist drugs for at-sea drop-offs. Smugglers tamper containers when vessels are departing from ports – e.g. across the Gulf of Guayaquil – or act in complicity with crew members of general cargo ships and bulk carriers to conceal drugs in vessel compartments. These are often attached to sea buoys and GPS tracking devices that are thrown overboard at sea. Receiving smugglers off western Africa or southern Europe then retrieve the cargo from the sea using semi-rigid inflatable boats or artisanal fishing vessels.

Another trend involves the use of parasites, which entail hiding drugs below the ship’s waterline. This technique either involves attaching metallic structures to the ship’s hull or hiding drugs within the vessel’s sea chest. This technique is prevalent in Brazil where prominent smuggling organisations are known employ divers to attach parasites in ports and then fly these individuals to the ship’s destinations to ensure a successful retrieval.

Similar incidents are rarely reported outside Brazilian ports, although this does not necessarily indicate a lower prevalence at other locations. Instead, it may be linked to diverse counternarcotics strategies employed worldwide.

Suggested precautions and operational measures

Drug traffickers are known to prefer shipping containers due to the difficulties around security inspections. Most containerised cargoes are either uninspected or port personnel lacks the resources to evaluate results of non-intrusive measures.

These challenges exacerbate as port terminals adopt automation and vertical integration to promote efficiency. However, it should be noted that smuggling groups are increasingly inserting themselves into the supply chain of large shipping liners, increasing the risk of detention and investigation should drugs are discovered while in transit or at the ultimate destination.

In addition, customs and security officials face escalating recruitment attempts by criminal groups due to a weak port governance. To address the threat of infiltration, maritime stakeholders should increase their collaboration with port authorities and local governments and ensure that increased security measures are adopted, including perimeter security, access control, anti-corruption programmes, strengthened protocols for cargo retrieval as well as law enforcement operations.

The widespread use of shipping containers can overshadow awareness of other ship owners or operators, making it less likely to revisit the vessel’s security plans or lean too heavily on under-resourced port facilities. To mitigate the threat, ship operators should consider the prevalence of smuggling operations in vicinity to port terminals, considering that unforeseen delays entail significant costs. Although sporadic, these vessels are used for drug smuggling attempts and crew members have faced lengthy prison sentences in the past.

Overall, ship operators should stay abreast of successful counter-smuggling strategies as it will most likely prompt smugglers to change the departure and/or destination ports as well as to diversify concealment techniques. Operators should also consider strengthening security watches and ensure that crew members are familiar with IMO guidelines for the prevention of drug smuggling.

Furthermore, escort services from coastguard units should be considered when sailing through areas where the cocaine smuggling threat is elevated. Escort services provided by law enforcement units are more likely to deter smugglers from the use of violence in contrast to the use of armed private services. The former is most likely to prompt smugglers to escape the scene to evade arrest, while the latter have sporadically led to criminals firing live rounds towards the ship’s bridge or accommodation area when noticing the presence of armed men on board of ships.

We thank Diego Briceño, Analyst with Risk Intelligence, for sharing his insights.