The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently warned that the strongest solar radiation storm in 20 years could affect Earth’s atmosphere, with potential disruption to communication and navigation systems. This article takes a closer look at what ‘space weather’ is and its implications for shipping and marine insurance.

Published 12 February 2026

The Northern lights are recognised as one of Earth’s natural wonders, with its bright, colourful displays across the Arctic skies caused by solar emissions interacting with the Earth’s magnetic field. While these displays can be beautiful, the solar activities that cause them can, if strong enough, interfere with critical technologies. As NOAA recently warned that the strongest solar radiation storm in 20 years is expected to impact the Earth, it is worth asking what shipowners should be prepared for, and which risks are covered by insurance.

What is space weather?

The term ‘space weather’ refers to a series of phenomena originating from the Sun, including solar flares, streams of charged particles and coronal mass ejections. In mild cases, space weather results only in auroras near the poles. In stronger events, it can disrupt satellites, navigation systems, radio communications and power networks.

The risks are well documented. In its 2025 National Risk Register, the UK government warned that severe space weather could disrupt “vital technologies”. Lloyd’s has also identified space weather as a significant global risk in their recent systemic risk scenario.

Why it matters for shipping

History shows the potential impact. In 1859, the Carrington Event – a strong geomagnetic activity – caused telegraph systems across Europe and North America to fail. In 2003, severe space weather disrupted GPS signals, damaged satellites and caused a full communications blackout in the polar regions. More recently, in 2022, it was widely reported that SpaceX lost 40 of 49 newly launched satellites as a result of severe space weather.

For shipping – increasingly reliant on electricity and satellites to power and guide navigation systems – space weather is a significant risk. During severe space weather, the changes in the earth’s atmosphere can impact the movement of satellites in orbit, create ‘phantom commands’ and put satellites fully out of operation. AIS, GNSS and GPS systems can be completely immobilised. Further, High Frequency and Very High Frequency communications can effectively go into ‘black out’ as radio signals are prevented from travelling through the Earth’s atmosphere. Such disruptions pose risks to both safe passage and effective emergency response.

While no vessel casualties have yet been directly linked to space weather, the risk is clear. A sudden loss of satellite and radio communication could easily contribute to a serious incident. The issue is even more pressing for autonomous or highly automated vessels, which depend heavily on uninterrupted satellite signals to operate safely.

Further, modern ships are equipped with sophisticated electronic control and automation systems. Solar storms have the potential to induce electrical surges in these systems, which can result in malfunctions, power outages or even permanent damage.

Impact on port infrastructure

The potential impact of space weather is not limited to ocean going vessels. Given its capacity to effect energy grids and power sources, space weather can equally cause damage to critical port and shipping infrastructure. Cranes, automated cargo handling systems, and power grids at ports depend on stable electrical networks. A significant solar storm can induce geomagnetic currents in terrestrial power lines, leading to blackouts or equipment failures that halt port operations. In 1989, an extreme surge in power caused by space weather had the effect of causing a blackout in Quebec for nine hours. The transformers in the nuclear generators further away in New Jersey were also burnt out by the same weather, leading to millions of dollars in costs.

Are the risks covered by marine insurance?

Should space weather result in damage to the cargo, it is likely (albeit legally untested) that space weather would fall under one of the Hague Visby defences, such that Owners should be able to defend claims on that basis. P&I cover for cargo claims, crew claims, pollution etc would not be prejudiced by the fact it arose from space weather.

Coverage for damage to the vessel’s equipment, hull or machinery caused by space weather may depend on the vessel’s specific insurance. Under ITC Hull clauses, which is a named peril cover, space weather is not included and so damage from space weather would not be covered without an additional perils clause being added to transform it into an all-perils cover. The Nordic Plan is an all perils cover, and space weather is not listed as an exclusion.

What should shipping companies do?

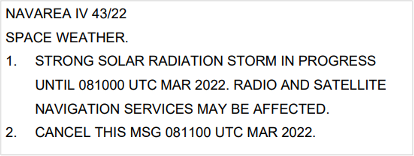

The good news is that space weather forecasting has improved significantly. Agencies such as NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and the UK Met Office now provide advance warnings and real-time alerts, similar to conventional weather forecasts. Solar storm warnings are usually also sent out via NAVAREA messages to warn mariners, as shown in the below example. These can help operators prepare for potential disruption.

Example of a Space Weather warning from ‘MSC.1/Circ.1310/Rev.2’.

Shipping companies can also take practical steps to reduce risk. As highlighted in our article on GPS jamming, crews should be trained and vessels equipped to operate if there is disruption to satellite navigation or electronic communication systems. For further details and input, readers may wish to refer to the newly published report from the Royal Institute of Shipping.

Conclusion

As shipping becomes more reliant on digital technology and satellite systems, space weather is an emerging risk that deserves greater attention. Severe solar storms are rare, but their potential impact places them alongside other low-probability, high-impact natural hazards.

For shipowners, managers and insurers – particularly those operating in higher latitudes – understanding space weather and preparing for its effects is increasingly part of good risk management.

The authors would like to thank Gard colleagues Louis Shepherd and Siddharth Mahajan for assistance with this article.